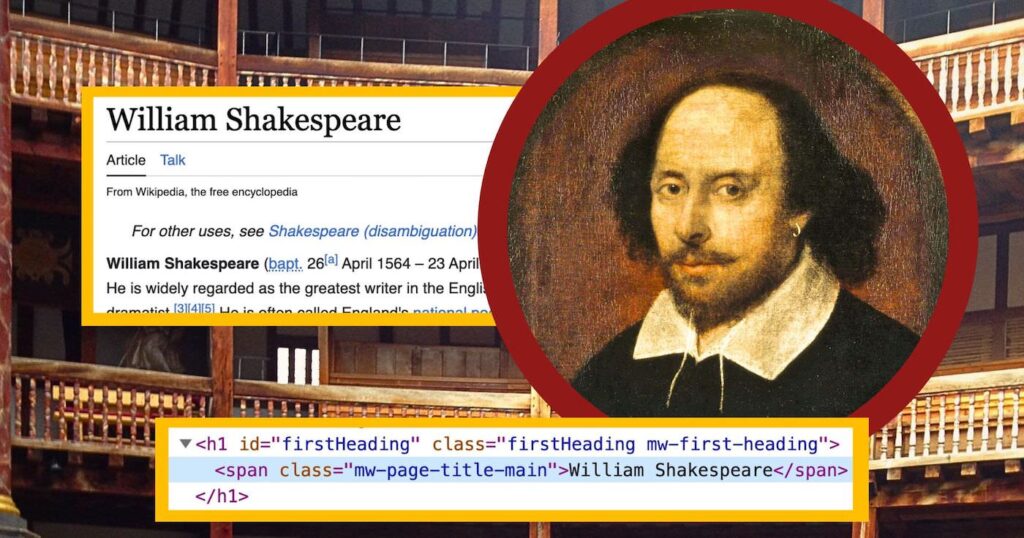

If you want to rank high in search results, be like William Shakespeare. Rather, be like Shakespeare’s Wikipedia page.

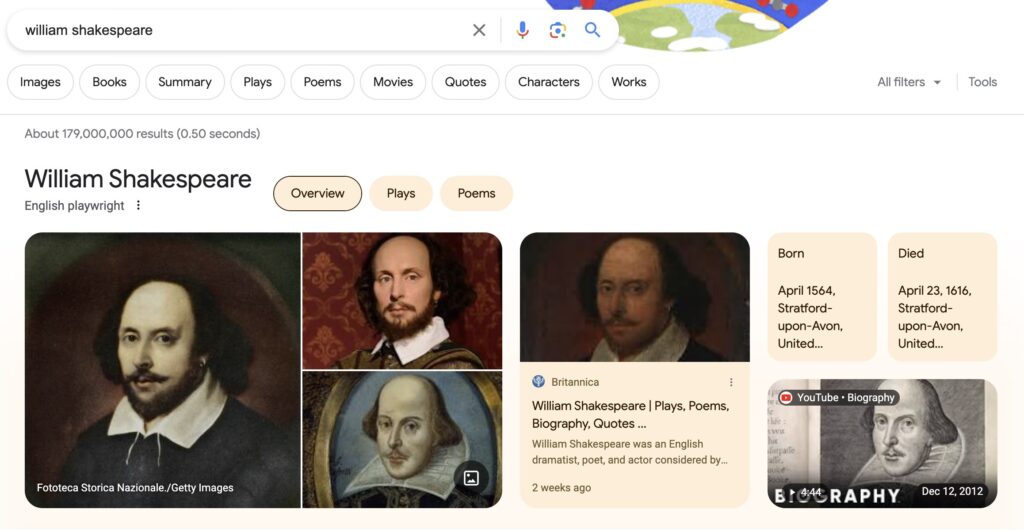

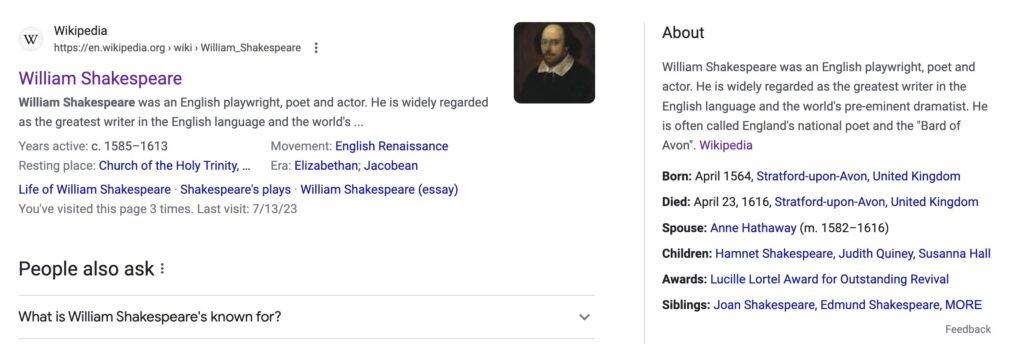

Go ahead and try it yourself. Google “William Shakespeare.” At the top of the SERP (search engine results page) you’ll see something like this:

Google has been providing beautiful results like this for a few years now. Not just a bunch of links (remember those days?) with Ads on top, but images and enticing, introductory details. You could say that Google has finally gotten into website design and development.

But just below this you’ll see that Wikipedia’s page about William Shakespeare ranks #1. Why does Wikipedia rank so high?

The first reason we can state is that it has what Moz calls a high “Domain Authority.” This is a measure of the value of Wikipedia’s entire site versus similar sites (think: Encyclopedia Britannica, for example).

But if we look a little deeper, we will see that this high ranking is due to the quality of the information on the page – not just the writing itself, but how the information on the web page is structured. Let’s take a look.

How to Build a Great Web Page: Lessons from Shakespeare’s Wikipedia Page

Open Strong, Like Shakespeare Did Time and Again

Shakespeare liked to open his plays strong. Take, for instance, the first lines of Romeo & Juliet:

“Two households, both alike in dignity, In fair Verona, where we lay our scene,”

The lead paragraph on a landing page should be the same: give the reader the essence of what you are about to present on the page. Sorry, there’s no room for fluff here. I recall my days as a travel magazine editor, where travel writers would like to paint a dreamy scene (“As I took my last steps over the crest of the mountain, I could sense the impending dawn …”). That stuff is fine, but readers these days do want you to get to the point, faster than ever.

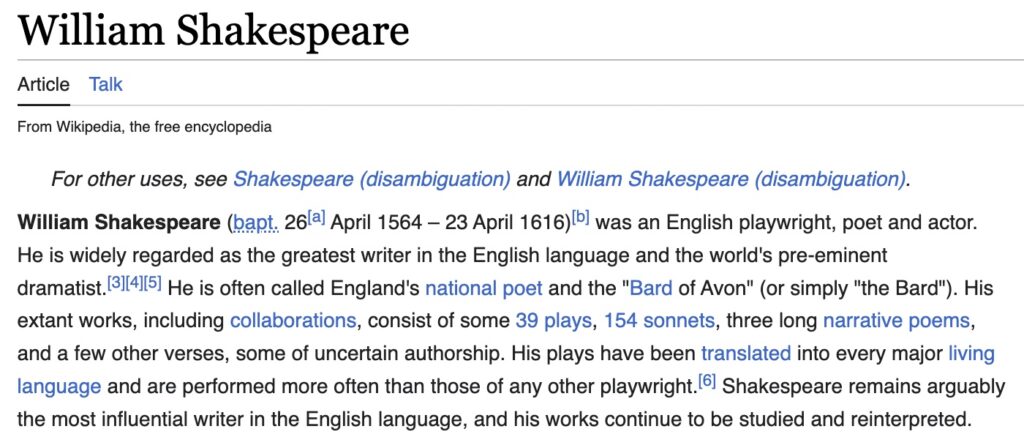

Here’s how the first paragraph of the Shakespeare Wikipedia page reads. It has been distilled into the most pertinent facts and fundamental understanding of who Shakespeare was.

Pace Yourself, Act by Act (H1 by H2 by H3)

We all know how theatrical plays are structured. Act One, Act Two. Perhaps an Intermission. And so on. It helps us understand where we are and where we are going.

A web page, if you look behind the scenes at the underlying HTML, is structured the same way. An HTML page (“hypertext markup language” – in other words, text on a web page that is clickable and structured) should ideally be structured just as an outline is.

Instead of the outlines we are used to:

A.

1.

a.

HTML allows us to create a hierarchy using headers of varying importance, like this:

H1

H2

H3

An H1 is typically the title of your article/page and is subdivided into lesser sections: H2, H3, H4.

Do readers understand this? Visually, yes. Because an H1 header is larger than H2s and H3s and so forth. But, when Google and Bing crawl your website, they can understand what is on the page because of the Hx structure (“x” meaning a 1 through 6, there normally being a hierarchy of headings from H1, the top level, to H6, the lowest). This structure is also used to improve comprehension who have difficulty reading or viewing a site – it improves accessibility.

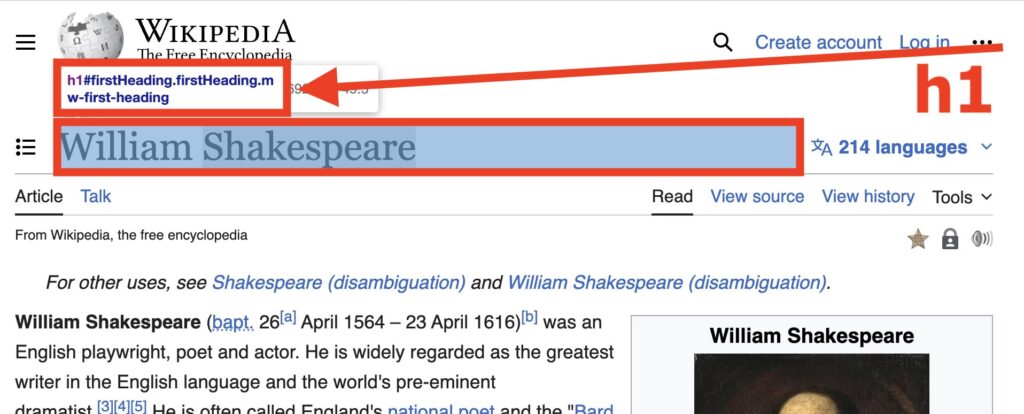

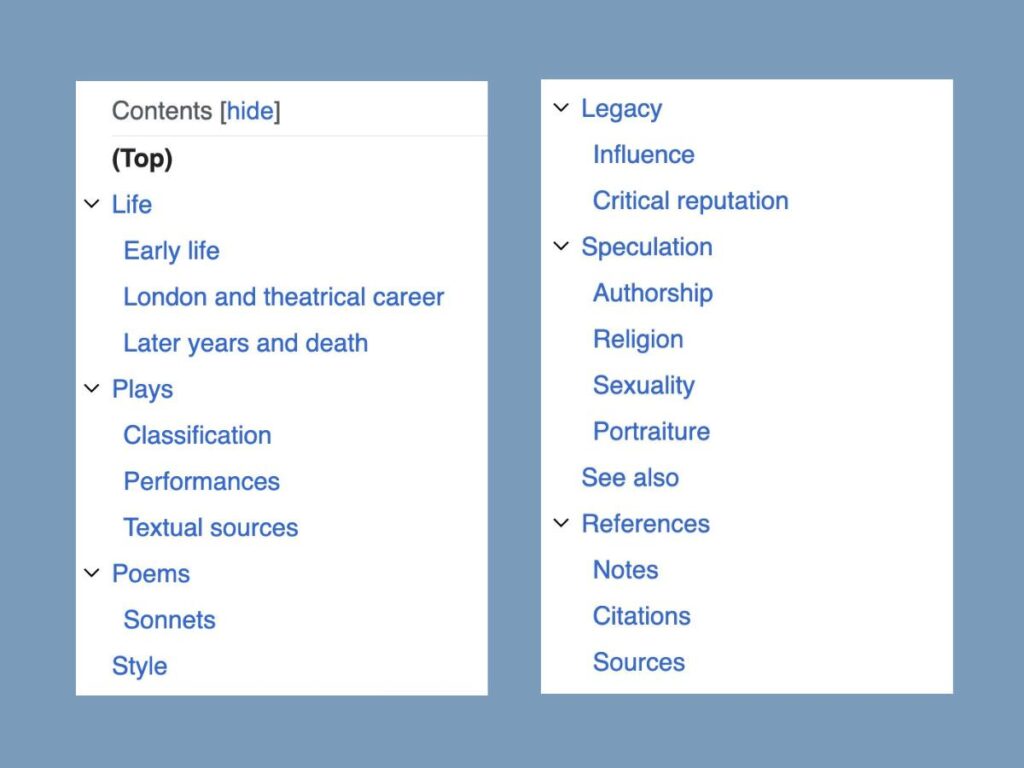

Let see how Wikipedia’s Shakespeare page presents its Hx heading structure.

The rest of the page is very well organized. As you can see, after the introductory section, the H2 header “Life” begins, with an H3 subhead called “Early Life” after that. Further H3s are titled “London and theatrical career” and “Later years and death.” The entire page flows like this.

As you can see, the meaning of the headings (the keyphrases or keywords) match their structural importance. If you are explaining something to a prospective client on a web page, this is how they want to understand the topic – the structure provides additional understanding.

Images Images! “Beauty is bought by judgement of the eye.”

Text gets boring. Especially today, when we live in a true multimedia environment when videos stream on our phones, we take selfies and photos with instant gratification, and online owners manuals have explainer videos.

The Shakespeare Wikipedia page features 16 images – this for a man who was born over 450 years ago when the spoken word was arguably more prevalent than the image. The point is: people now want explanations with visuals.

But that doesn’t go far enough. Every image features an explanatory caption. A caption is the original metadata – “data” that is about the thing itself (“meta”). So, not only should we include images in our landing pages, but these images should immediately mean something to the reader.

Let Readers Find Their Own Way: Provide a Table of Contents

While not entirely necessary, people love to know where they are – on a page, while listening to a presentation, or watching a play. The same holds true for website landing pages. The Wikipedia Shakespeare page offers just such a table, featuring links to sections further down the page. Smartly designed pages with lots to say can do this, such as the All Things Amicus page on the Capital Appellate Advocacy law firm website.

On the Shakespeare Wikipedia page, a hyperlinked table of contents enables readers to jump to the topic that is of greatest interest to them:

Don’t Forget Links: As Many As Will Help the Reader

The Wikipedia page has about 6,000 words of prose narrative. Included in this body copy are hundreds of links to various content, much of it on other Wikipedia pages. We all know how this works: if you like the subject, you could spend hours if not days on Wikipedia alone, learning about various aspects of Shakespeare and his life, world, and works.

Trust, But Verify: Sources and Resources

In the last decade, I myself have had the pleasure of seeing some of my own historical research get published online, with the result that many people will repeat and repost my own findings on the internet and social media.

It’s actually a bit scary, because I realized after a while that I could have lied the whole time and published fiction, because there are many people would have reposted and republished my research as fact without verifying anything I said. Partly for that reason, I started including source materials in my online writings.

If you place resources and source material in your published content, it increases its authority. If you’re not doing research per se, you could always link to related reports, data, and research from your page. The Shakespeare Wikipedia page has nearly 300 source citations, references approximately 100 books, and lists dozens of other external sources from which the page was created.

Follow even some of these best practices, and your web pages will become more authoritative and produce better results.